PreservationAn Endangered Breed

As early as 1789, the Spanish controlled the export of ewes from the provinces of New Mexico to maintain breeding stock. But in the 1850’s thousands of Churro were trailed west to supply the California Gold Rush. Most of the remaining Churro of the Hispanic ranches were crossed with fine wool rams to supply the demand of garment wool caused by the increased population and the Civil War. Concurrently, in 1863, the U.S. Army decimated the Navajo flocks in retribution for continued Indian depredations. In the 1900’s further “improvements” and stock reductions were imposed by U.S. agencies upon the Navajo flocks. True survivors were to be found only in isolated villages in Northern New Mexico and in remote canyons of the Navajo Indian Reservation.

Restorations of the Breed

In the 1970’s several individuals began acquiring Churro phenotypes with the purpose of preserving the breed and revitalizing Navajo and Hispanic flocks. Criteria for the breed had been established from data collected for three decades by the Southwestern Range and Sheep Breeding Laboratory at Fort Wingate, New Mexico. Several flocks have developed, and the Navajo Sheep Project has introduced cooperative breeding programs in some Navajo and Hispanic flocks.

Conservation

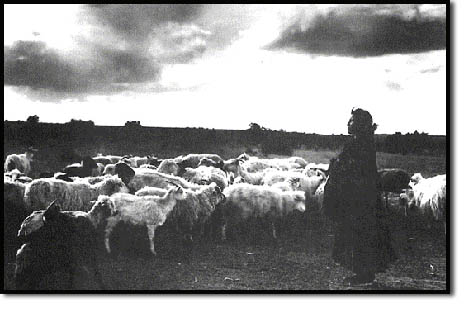

The Dine’ were initially responsible for saving the “old type” sheep from extinction. Navajos successfully maintained original flocks in isolated areas where no other sheep breeds were introduced. Sheep meat, milk for yogurt and wool for textiles sustained the Dine’ for centuries. Even today, “Sheep is life,” is a strong belief in traditional Navajos.

In 1934 the U.S. Department of Agriculture established the Southwestern Sheep Breeding Laboratory at Ft. Wingate, New Mexico to determine what sheep might thrive in that region. They assembled some “original old-type” Navajo sheep from local flocks and for 30 years introduced fine wool breeds and long wool breeds. They concluded that the best wool for the weavers and the sheep most suitable for the high desert were the “old type”.

By 1977, the “old type” Navajo sheep had dwindled to less than 500 head so Dr. Lyle McNeal formed the Navajo Sheep Project to revitalize this breed and keep it from further depletion. Through the efforts of individuals such as Ingrid Painter, Dr. McNeal, Antonio Manzanares, Maria Varela, Goldtooth Begay, Dr. Annie Dodge Wauneka, Milton Bluehouse and Connie Taylor with the assistance of conservancies such as the CS Fund and American Livestock Breed Conservancy and Ganados del Valle, the Navajo-Churro Sheep Association was formed in 1986. There are currently over 4,500 sheep registered with the N-CSA, an estimated 1,500 on the Navajo Reservation and several hundred undocumented sheep in the U.S., Canada and Mexico.

Breed standards were developed for conformation and wool characteristics using historic records, oral descriptions from Navajo Elders, the contemporary Spanish churra and research from the Ft.Wingate project. This included objective measurements by USDA scientists and subjective observations of the samplers woven and dyed by Navajo weavers employed at Ft. Wingate. Individual breeders located sheep sifted from the remnant flocks of the Southwest and West Coast and a few sheep still existed at UC Davis in California. “Wanted Posters” were used by Dr. McNeal’s Navajo Sheep Project to increase awareness of the breed and to locate old type sheep for a revitalization of the nearly extinct breed. Historic standards were applied to the existing nucleus of all the “old type” sheep that were located.

In 1986, the N-CSA began registering Navajo-Churro based on phenotype. The registry process is vital to maintaining standards and providing breeders a network of pedigree information. Even though standards are used, there is an attempt to maintain the diversity within this landrace population. Each sheep registered must be “seen” and approved by on site inspection or by mail in photos and fleece samples. All progeny must be inspected for registration, even if parents are registered. The inspectors must have competence in sheep and wool. Several on the team are university professors or County Extension Agents who specialize in sheep. The flock book remains open to all conforming sheep even if they lack pedigree information.

Inbreeding is not a problem except in a few flocks. Committed breeders pay attention and share transportation expense to long haul stock. Genetic relationships for 2,845 sheep were calculated by Harvey Blackburn, U.S.D.A. to calculate inbreeding levels for individuals and for flocks. The average for the population was 3.8% in three generations and increasing. A few flocks had levels of 10.5%. Breeders often refer to “A Conservation Breeding Handbook” by ALBC for advice on sound breeding schemes for small populations.